Why Europe’s banks want to end US dominance in payments - Financial Times

The last time Europe's banks tried to build a payments group capable of taking on the US giants that dominate the sector, they failed miserably.

But when Project Monnet collapsed in 2011, nobody was talking about the commercial threat from US tech companies; and the EU's politicians had not just lived through the Trump presidency.

Now, with those politicians convinced that a European payments system is a question of sovereignty, some of the currency area's largest lenders have teamed up to launch a new attack on their dominant US rivals.

It got off to a rocky start last summer when US soft drinks group PepsiCo objected to its proposed name: The Pan-European Payment System Initiative, or, PEPSI.

However, key backers are still optimistic that the idea, now dubbed the European Payments Initiative, can succeed.

In 2011 "there was no political support at all", Wolf Kunisch, head of strategy at Paris-based payments processor Worldline, told the Financial Times. Now "the European Commission and the European Central Bank . . . understand that to have European sovereignty you also need to have European payment systems in place".

The realisation that a US president on any given day could decree Mastercard or Visa should no longer do business "with a certain part of the population . . . that is too much of a dependence", said Kunisch.

EPI is backed by 30 banks and two of the continent's largest payments processors. It is tasked with creating a pan-European payments service that can be used to pay online as well as in stores, to settle bills between individual consumers and to withdraw cash at ATMs.

It is also designed to break up what its chair Joachim Schmalzl calls a US-dominated "oligopoly". Europe's banks are considering their own interests, aware that if they do not act now, they could be challenged by tech companies such as Apple and Google that are increasingly on their turf.

"If we don't build a European player in payments today, it will be either Chinese or American [calling the shots]," Philippe Heim, the chief executive of France's Banque Postale, told the FT.

And Schmalzl, who is also a board member of the German Savings Banks Association, the country's biggest retail banking group, warns that those rivals would "increasingly take away market share" from European banks.

A clearer profit motive

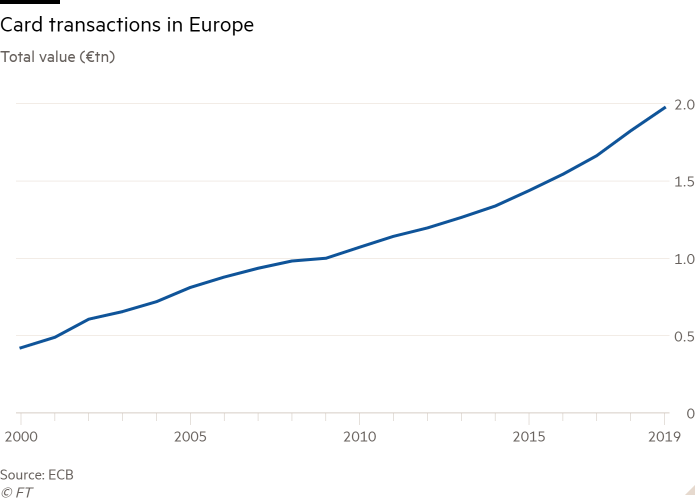

Today, four in five transactions in Europe are handled by Mastercard and Visa, according to EuroCommerce, a lobby group of European retailers. While on the other side of the table, the banks and acquirers driving EPI currently process more than half of all EU payments.

The critical mass of business brought by banks such as Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas, ING, UniCredit and Santander give the EPI weight. The Brussels-based entity has until September to draw up a blueprint. If the banks behind EPI then give the green light, the first real-world applications could be launched in early 2022.

Some obstacles that brought down the 2011 Monnet project have disappeared. Back then, European banks owned Visa Europe — an independent company until it was bought back by its parent in 2015 — and were reluctant to build a competitor. Now the profit motive is clearer.

"If it is our tool, it means that the margin is ours. Because we have seen that with Visa Europe or Visa Inc, or Mastercard at the end of the day, the financial conditions are imposed on us by the big operators," said Heim.

Working groups are meeting weekly to try to hammer out the shape of the EPI but there are still significant hurdles. "It is not the case that the world has been waiting for another player that offers additional [payments] solutions," said Schmalzl, adding that EPI's products "of course need to be as customer friendly, if not better" than the offerings from Visa, Mastercard and PayPal.

How to build a customer base

EPI also faces a simple chicken and egg dilemma. For a system to work, you need merchants ready to accept payments and users ready to make payments. Having both in place at the same time is not an easy task, particularly since the full rollout could take years, and a bad start could kill EPI's chances of success.

As one senior French banker involved in the project said: "It took a decade and a pandemic for contactless payments to really get going."

A key question is if the German and French banks will be willing to migrate existing national payment schemes — Girocard in Germany and Carte Bancaire into EPI. "Without a credible commitment to do so, EPI won't be able to succeed," said a German banker involved in the discussions.

National pride, and the fear of replacing established payment systems with an unproved alternative, are still formidable obstacles, people familiar with the project warn.

On the other hand, bankers fear that the domestic schemes do not have a future on their own. "Girocard has been suffering from at least a decade of under-investment," said another payment expert working at a big German lender, pointing to the fact that the system neither works online nor abroad.

A senior figure at a French bank agreed, saying that if card schemes in France did not grow to a European scale they "would be dead" in the next 10 years. The executive expected cards to start migrating to EPI in 2023.

"What EPI needs is someone to take leadership," said the German banker, as even the co-ordination between the various German lenders that are participating is "painful and ineffective". The need for consensus, they said, is time consuming and often results in agreeing on "the lowest common denominator".

"The biggest risk," said another French banker on the inside, "is that those involved eventually decide it's too complicated and decide to leave."

Questions of competition and compromise

One example of the need for compromise trumping commercial sense is the location of the EPI's headquarters in Brussels. "That choice looks like a political decision," said Marcus Mosen, a payments consultant and former chief executive officer of German payments firm Concardis, adding that on purely commercial grounds, Berlin, Paris or Amsterdam would have been a better choice.

For now, EPI's backers have forked out €30m — a decent sum to fund the initial development of a blueprint, but way short of the "billions of euros" that Schmalzl deems necessary.

Bankers in Germany and France agree because, as it stands, the EPI shareholders will have to bear the cost of development and the potentially high transition costs, such as cancelling contracts and swapping out cards, for users and merchants.

One way to defray the costs could be to tap EU funds. "We believe that in supporting infrastructure in Europe, one should not just build roads, but potentially also 'payment roads'," said Schmalzl.

However, banks are also concerned that EU funds could come with strings attached.

And while European policymakers have given the EPI a green light, bankers are concerned about competition stemming from plans for a digital version of the euro.

The ECB's planned digital currency, itself partly conceived as a way to improve cross-border payments, could be in direct competition with the EPI and therefore eat into bank margins. But as one senior Eurosystem official said: "We have to think about consumers, banks and the overall financial system. So, the banks should do their jobs and we'll do ours."

But despite the difficulties, European banks and payment processors are optimistic that this time will be different. Although the scheme currently only has banks from six countries on board, people close to it are hopeful others will join soon, including Italy.

And Kunisch is ready to bet on EPI working: "Our real assumption is that this will happen. And I don't really see any fundamental deal breakers coming up. But if you'd asked me to put €100 on this, I'd put it fully on the side of this happening."

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire